John Pexton Clark was born in Hedon, Yorkshire on Sunday 27th of August 1916 to William and Elsie Clark.

Growing up he developed a passion for sports, especially athletics, holding his final record as Black Heath Harriers Running Club’s oldest surviving member.

When he was called up into the Army, John was living in London and working for the Land Registry where he, funnily enough, worked in the same office as his future wife Delys.

Known to all as a kind, thoughtful and highly intelligent man with a great sense of humour and an enormous interest in the natural world, qualities which he never lost.

This book is the full detailed account of the war kept by John, written up and designed by his granddaughter, Kirsty, in December 2019.

It is impossible not to be inspired by his humanity and observations of life, death and camaraderie; a true account of an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances.

My army career started on the 16th of May 1940. Eric and I were called up on the same day, he went to the R.A.M.C., myself to the R.A. Signals at Colchester.

The first few days were spent in waiting for stores, clothing, medical and dental inspections and inoculations, also an address by the C.O., a Major Maxwell.

Colchester Barracks are dingy and brick-built, with iron beds, and designed with the Cavalry in mind. The town itself is pleasant enough. Plenty of pubs: The Cups, The Fleece, The Dragon, The Cross Keys, and Canteens at the Moat Hall and St Peters; plus numerous little cafes and pie shops, which all became familiar during the next few weeks.

After two or three days we started our training in earnest. Marching, P.T., elementary Gunnery and Morse. Gun-drill was done on an old 1914 War 25 pounder and limber, though this was taken away from us after Dunkirk and given to an active Regiment.

If we were short of weapons we were well off for Military Bands. There were two: one a Cavalry Band who played on the Barrack Square, and we were drilled to martial music on several occasions.

Includes:Marching, Rifle, and Gun Drill plus relevant abbreviations

Includes: The Morse Code and learning aids

All the lads were willing to learn and get preliminary training over. I was drafted to Squad 36a, most of whom were Newfoundlanders and all volunteers. They were an exceptionally friendly and likeable lot and we got on well. These boys were all far from home and some were homesick and already becoming a little frustrated at all the bull we as recruits, had to go through…

There were one or two air-raids and by the 10th of June the German Tanks were in Rouen and Italy had declared war on us – the situation was pretty grim and invasion became a reality. It was on the 12th of June that we were split up into rifle parties and given infantry training, here we did several night exercises and made mock raids on imaginary parachutists: with rifle and bayonet!

It was quite an experience to be out in the countryside and under the stars on those summer nights. The scents and sounds were extremely peaceful and the terror of war seemed far away. I remember one particular moonlit night when we put down our blanket on an open Sports Pavilion veranda, with roses in full bloom rambling almost over our faces – pleasant indeed, but I shudder to think what would have happened if any of our alarms and excursions had been for real.

” The scents and sounds were extremely peaceful and the terror of war seemed far away “

I cannot remember much about my fellow recruits though we spent a lot of time together, in fact the whole squad lived together day and night. We all slept in the same Barrack room, drilled and trained together and spent the evenings in the pubs in Colchester. Only some of their names stick: Moekler, Parsons, Walsh, Burke, Flynn, Harris, Facey, and Cochrane.

On the 12th of June I was told I was to be posted to a Survey Training Regiment in Brighton, and the following day myself and Sid Garrad were packed and ready to go. We got up about 5-30am, paraded in front of Depot Battery, then were taken to the station by car and arrived Liverpool Street at 10-30am.

Sid’s people were waiting for him and after arranging to meet at Victoria about 1pm he went off. I rang Mum and while I waited for her, went into the office at Lincolns Inn Fields to see the lads and lasses. Graeme goes to Skegness on Monday. Mum and I had lunch at the Corner House, and then I caught the 1-48pm to Brighton arriving at the Barracks in time for tea.

It was a laughable sight to see Sid coping with a heavy pack and two huge kit-bags – a friendly postman gave him some assistance. I let my kit bag roll down the steep incline from the station, it certainly gathered momentum but unlike the rolling stone gathered a considerable amount of dirt, finishing up on the London Road.

‘The Palace Pier: the finest Pier in the world’

Note: polished boot toes and carrying gas mask and steel helmet with bathing things inside

On the next day after we had a cursory Medical inspection. It went like this.

M.O: ‘You all right Clark?’

Me: ‘Yes Sir!’

M.O: ‘Very well, Next please’

Immediately after this, I was picked for Guard Duty on West Pier – I was inspected and paraded, then taken down to the Pier in a lorry. The changing of the guard was apparently looked upon as something of a spectacle and the Sergeant was intent on giving the already assembled crowd their money’s worth.

The ceremony over, I could take a look at the surroundings. The original Pay Box at the Pier entrance was now the Guard House and the ladies’ toilet was the Mess. It turned out to be a lovely night: clouds scudding along calm sea, wind off-shore and the moon making silvery reflections on the water. As this was a 24-hour Guard, we had the whole day as well as the night to spend here.

Though at night there was no distraction from the sounds and beauty of the sea and sky, during the day, as the front was still open to the public, it was amusing and entertaining to see and sometimes to talk to the passers by. It was quite the usual thing to get presents of food, fruit, books etc. from these people. One old lady with a Pekingese [dog] made an anxious enquiry as to what had happened to the Pier cat… From what has happened to the Slot Machines and locks and safes, I should not be at all surprised at what had happened to the unfortunate cat!

We were relieved at 6-30pm by the new Guard and so back to Barracks.

Our days and nights for the next month or so were repetitions of Guard duties, marching drill, rifle drill, interspaced with various fatigues, and one or two alarm excursions.

One such was when I was going out on an evening pass, all leave was stopped and we were detailed to collect our rifles, and boarded a coach and driven, first to Shoreham Harbour, then to the Gas Works, on to the West Pier and then visited a Naval Battery, all in a night drive, finishing up in the early hours at an empty house in Portslade, where we all got down on the floor for a short rest, no food or drink, except a cup of tea from a kind lady in a house in Grange Road called ‘Minihaha’. Eventually we got back to Barracks to find ourselves on Guard again.

On another occasion we were taken by coach to Preston Park, where we got down among the trees for the night, but at 1-30am were told to get back to Barracks. Tempers were rather frayed that night. It started at the beginning, when a few of this Mobile Squad took longer than the quarter of an hour allowed, from hearing the signal to parade, and ending by someone putting his rifle through one of the coach windows, and yet someone else dropping a box of Molotovs, breaking the lot with petrol all over the place.

We never took these excursions very seriously, which with hindsight, knowing at the time a German invasion imminent, could have been a devastating shambles.

” We never took these excursions very seriously, which with hindsight could have been a devastating shambles “

On the 5th of July the front and foreshore were closed and we started to strengthen the shore defence with pathetic sandbagged positions, all the way down to Rottingdean. Rumours of an invasion were numerous, even that bodies of German soldiers had been washed up along the coast.

By this time there was evidence that the coast defence around here needed to be stronger than the rifles and Mobile Squads of our Training Regiment could manage. The 3rd Field Regiment came in somewhere at the back of the town, and calibrated their guns, and registered targets along the seafront. A Machine Gun Regiment went into Rottingdean, and took over our small amateurish positions in that sector.

Though there were rumours that we were going to be relieved guard duties, we still alternated with very little respite from these duties, between Palace and West Piers. We grumbled and lost a lot of sleep, but the nights, and early mornings especially, were often magic, the moon, the sea, the sun and clouds, and the wind and surf.

We sometimes did a guard duty at the Barracks. This was a prison cell of a place, and in fact had prison cells for any delinquents. Guard duty here was a claustrophobic experience. Standing outside a door under a veranda, and facing a blank wall, the only opening being a barred Wicket gate which opened onto the street.

” The nights, and early mornings especially, were often magic, the moon, the sea, the sun and clouds, and the wind and surf “

There were a few regular soldiers on this guard and it was here I came across the system of one of the guard being nominated by the Inspecting Officer as ‘stickman’. If you were awarded this you did not have to do any guard duty as such and were able to sleep all night without interruption, merely acting as runner during the day. The criterion for this award was to be judged the smartest and cleanest on parade. This often meant some regulars had a complete outfit cleaned and pressed including boots boned to the gloss of patent leather, and even the studs on the soles polished, all reserved for these occasions. Some even went to the length of getting two pals to carry them onto the Parade ground, and put them down in line with others on parade so as not to get even a speck of dust on their boots before the inspection took place.

We recruits were no match for the Regulars at this game, though some caught up very fast. However, none of us escaped having to do some spit and polish bull. The technique of using the back of a heated spoon to bone the toe of the boots with a mixture of boot polish and spittle, and eventually obtaining a mirror-like finish was an early achievement. But the bane of the week was the Barrack Room and kit inspection. First, the floor, which was wood blocks, had to be highly polished. To this end we had to collect a huge dollop of polish from the Stores, usually in a few sheets of newspaper. This had to be spread over the floor, this was then polished until it shone, with a heavy padded metal bumper. This was really hard labour. After this beds, bedding and kit had to be laid out in accordance with the official kit layout. There were no prizes for all this, but plenty of punishments if things were wrong.

On the 11th of July 1940 Mum and Dad came down to Brighton. Saw them at lunch time and arranged to meet them in the evening. We had dinner at Howards Pavilion Restaurant, very civilised and pleasant change.

Around this time, we had a spell of contrary weather, beautifully clear and sunny, with high gale force winds, alternatively rising, and the next day dropping to a mere breeze. These winds, coming from the sea lashed up the waves and at high tide, sending spray swilling and sparkling over the Pier and us, drenching the whole front. It reminded me of Robinson Crusoe’s comments in his diary, “The night before, a terrible storm, and the day following calm and sunny”. For us the significance of these conditions, was that whilst this weather lasted, invasion by sea was improbable.

By the middle of July we were finally relieved of guard duties, and our Survey training started. Also the beach and foreshore were reopened between the Piers, and on our afternoons off, several of the Squad used to go for a swim, and perhaps tea afterwards at the Mikado café on the front, where they boasted that a huge Willow patterned bowl on the counter, was always full of cream.

” The significance of these conditions, was that whilst this weather lasted, invasion by sea was improbable “

Later we sometimes went to the Arlington for some food. This was a five-star joint and even at this time, luxuries like lobster and pheasant could be ordered. It was a favourite place for our Officers, and it was amusing to see to see, at the next table, a group of new recruits who had been put on cookhouse duties in the Barracks having a complete change; and knowing what it was like behind the scenes, back there, could appreciate what a drastic change it was. They even asked for French mustard. At this time, we had three Solicitors, one Barrister and three Surveyors, in the cook house. All volunteers to join the Army.

In early August there was a lot of air activity over the Channel, and our Regiment were recalled to do beach defence again. The Piers were cut, about half way down, and we did a lot of sand-bagging both at Black Rock and Shoreham. Though we were told these strong-points had got to be built, we were not given any material, other than sandbags. Everything else had to be scrounged, even tools. One instance, where a supply of nails was required, we went to a plumbers and house decorator’s place, who we knew had lent a garden fork to us about a month previously, and had not got it back, so here is the scrounge technique: ‘We understand that you lent us a fork etc. What is is like? Any markings? Will check up on it for you, and by the way have you a few nails?’ Easy.

On the 14th of August I had an interview with the Colonel, Pring-Mills, and was promoted to Lance-Bombardier. He told me that if my progress continued he would recommend me for a Commission. On the following day the new intake was due and I was put in charge of one of the Squads, and overnight became a father figure and mentor, and looked upon as an authority on such military matters as boot polishing, correct dress, kit layout, inoculations, and drills etc.

On the 14th of August I had an interview with the Colonel, Pring-Mills, and was promoted to Lance-Bombardier. He told me that if my progress continued he would recommend me for a Commission. On the following day the new intake was due and I was put in charge of one of the Squads, and overnight became a father figure and mentor, and looked upon as an authority on such military matters as boot polishing, correct dress, kit layout, inoculations, and drills etc.

One day we had a seven-mile Route march up to Moulescoomb, Falmer, Race Hill and back. It was exceedingly hot work in the sun, and shattered some of the recruits, but the Sergeant in charge was in no mood to spare them, as when we got up onto the Downs above Falmer the Air Raid sirens were heard over Brighton, and an enemy bomber came over, the squad, thinking that they were the special target of this lone plane, broke ranks and rushed for cover. One bloke had the temerity to drop his rifle, leaving it where he dropped it, and continuing his dash. The Sergeant was livid, as he had not given any orders, and so obviously the squad had a lot to learn, as to the bloke who had dropped his rifle, he could regard himself as a criminal and could think himself lucky not to be put on Court Martial, and shot! By the time things had been sorted out, the all clear had sounded, and the plane no doubt was back in Germany.

Thank God we have a Navy.

” Thank god we have a Navy “

From the beginning of September, we concentrated on our Survey training, the routine being, half an hours P.T. before breakfast, then lectures from 8.30am to 7pm in the evening. Sometimes we would do field work, perhaps out to Stanmer Park for map reading, and other days doing a traverse, and fixing gun positions, usually up above Falmer on the South Downs. The weather was good and we enjoyed these schemes. There was a lot of air activity at this period, and we saw many dog-fights high up in the sky, where the machine-gun fire, the vapour trails, and the occasional sight of a fighter plane dropping out of the clouds, and then zooming back, engines screaming, at incredible speed, made us realise that there was a real war on.

On the first of October I heard that [my sister] Marjorie had been taken to the north Cheam Hospital with T.B., but thoroughly relieved that they say that it has been caught in time.

Spent a lot of our half-days off, at this period, playing golf at Rottingdean, and afterwards to the Black Horse or the White Horse on the front. Sometimes we got further afield and walked the South Downs from Pyecombe to Lewes. At night if you walked up to Hollingbury, you could watch the fireworks of the London Barrage.

During October the staff at this Barracks was reduced, and towards the end of the month we got the order to move. The Regiment had a special train, which took us to Amesbury, our destination being the School of Artillery, Larkhill. It was a glorious day and the countryside was at its best, it was difficult to remember we were in a war. That night we were quartered in a Gymnasium, it was a freezing place. I met Braithewaite, and we went to the Garrison Theatre in the evening. He moves out on Thursday.

The next day, the 22nd October 1940, we wandered around the camp, getting our bearings. There was nothing but Military Camps and open plain as far as the eye could see, except for Stonehenge in the bottom of the valley, looking quite insignificant in the middle distance. The scene in the early morning is unforgettable, the mist clings to the valley, and the clumps of trees on the tops of the highest parts of the rounded Downs, stand out like islands, from this sea of mist. With the sounds of each Regiment’s bugle calls for reveille, some near, some afar, you realise that you are indeed a soldier, and following the long tradition; it could be any time in history.

We were soon organised in our new quarters, and continued our training. Rounds of angles, Knighton Tanks, Bulford Clump, Umbrella Tree. First swinging right, then left, hopefully checking out. All centred on the object of hitting a target which was perhaps miles away, and was invisible from the guns.

At the end of October, I had a few days leave, and went home to Norbury, along with a pal called Field, in his car. Several of the recruits still ran their own cars. Came via Andover and Basingstoke, had a meal at the White Hart, in Andover. Arrived home just after tea-time, much to their surprise. Had a quiet night, only gunfire and distant bombs. Next day Graeme turned up, he was on leave for ‘boiler cleaning’.

Back at camp, the weather was becoming very much colder, and it was not quite so pleasant having to do surveying out of doors, all day long. However, we eventually took our Trade Test, and I think most of us passed. So we ceremoniously sewed our ‘S’ badges onto our sleeve, and were given 1/- [one shilling] a day extra pay.

Our leisure time was spent, mostly in going out for extra grub, and a lot of beer was consumed. Sometimes in nearby Durrington or Amesbury, at other times going into Salisbury. Our favourite place for food was the village hall at Durrington. This canteen was run by the Ladies of the district, and the menu here was first class, sometimes there was trout. The excellent cooking, the general appointment, and the tasteful crockery and table decorations, so vastly different from Army and N.A.A.F.I. catering, made it well worth the three mile walk across the plain, even on a rainy night. On top of this could also be incorporated a drink at the Stonehenge Inn, either on the way there, or on the way back, or both.

Our training finished we then awaited our posting to serving Regiments. During this time, I had another period of leave and went home, hiring a car to get about. Visiting Hayes for a run over the country. But I spent most of the time indoors, in front of the fire, as the weather was decidedly December-ish, and it was a pleasant way to spend a few days.

Not long after I got back to Larkhill, my posting came through, and things happened very quickly. We were even measured for tropical kit, and given Pith helmets, and a rail ticket to Edinburgh. We had to report to the 94th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery.

There were three of us destined for this Regiment, Rigby, Burbridge and myself. Rig was a Surveyor with the Arnold C.C. Roger Burbidge was slightly older than Rig and I, and was a Surveryor with the Railway Company. He was a short dapper figure, with quite a sharp manner, and became known as the ‘Colonel’, but we got on very well together.

” Not long after I got back to Larkhill, my posting came through, and things happened very quickly “

We started away from Larkhill about midday on the 14th of December, arriving Crewe via Bristol, after travelling for 12 hours. Here we had a meal at the Y.M.C.A., and then caught a train at 3am Sunday morning, for Edinburgh. A lorry then took us up to R.H.Q., out of Colinton Way. Here we were given a meal, and as there did not seem to be any restrictions or duties, after tea we went out into town, and saw a concert in the Usher Hall.

” There did not appear to be any use for us Surveyors “

There did not appear to be any use for us Surveyors, and for a time we had nothing to do, and went into Edinburgh almost every day and saw a lot of films and theatre shows. Also became proficient at the game of Croquet, which we played on the lawns of R.H.Q. in Polwarth Terrace.

Just before Christmas R.H.Q. moved into a larger property in Ettrick Road, this was a large stone built mansion in its own grounds, including a tennis court and aviary. We called the place ‘The Towers’, though there was only one square central castellated tower, on either side of which were wings, each finished by stepped parapets to the gable ends: a most imposing building.

Polworth Terrace, Gilsland Road, Edinburgh

Left to right: Rig, Me, Rodger

Back left to right: Collur, Dyson, Gray, B.Kellet

Front left to right: ?, Stan Brett, Wood, G.Mold (killed in Italy)

No-one seemed to know what to do with us Surveyors. This Regiment is a local T.A. [Territorial Army]Regiment, and is being reinforced before being sent overseas, and from being wholly Scottish, is now being diluted by all us Sassenachs. There is a most un-military atmosphere, as all the originals know each other personally, and their civilian status, rather than their military rank seems to count most. A we newcomers only know the army rank, the situation is sometimes amusing.

We have plenty of time to explore Edinburgh, and it is indeed a fine city. There are many vantage points to overlook the town. One place, high up above the station, especially at night, where far below the trains run in the cavernous depth, the darkness accentuates the unprotected murky depths of the cutting, full of steam and noise.

On Christmas morning, of all times, we had to go through a gas chamber, for gas mask drill, with the usual lark of having to remove our masks in the thick of it. Everyone came out with their eyes streaming with tears. At the parade after this, the Colonel wished us all a Merry Christmas, he too had tears on his cheeks. After this we all went to dinner, it was a really special spread. Turkey, and all the trimmings, pudding, sauce and mince pies. Afterwards we had a sing-song, accompanied by fiddle, guitar, piano and accordion.

We have now been with the Regiment for a fortnight, and have done nothing but eat, so it was a change to be asked to help in the Office, and take over the switchboard.

On New Years Eve 1940, everyone was given a late pass until 2pm, and we went to Town to see for ourselves, how the Scots observe their festival. We had a few drinks at several pubs, but it started to snow, and within half an hour there was a layer at least two inches thick. Trailing between pubs wasn’t very pleasant, so decided to go to a dance at the Palais.

” On New Years Eve 1940, everyone was

given a late pass until 2pm “

When we got there it was crowded, and several of the natives were already under the tables. The floor got increasingly crowded, so we went up on to the balcony for an ice. What a sight it was from above, a seething mass of bodies. If these had been birds or insects, we should have assumed that they were about to swarm or migrate; perhaps true of people too, as we were expecting to go overseas at any time. A running scrap developed on the dance floor below, a sailor put up his fists, and engaged a soldier to fight. The soldier didn’t take much egging on, because he took a hefty swing at the sailor but missed altogether, and before he could recover his balance, some other bloke caught him a beauty on the chin. The mediators entered in at this point, and held the contestants apart, but they broke away, and the last I saw was a struggling heap on the floor. After the dance we made our way back to the R.H.Q., through the snowdrifts. What a tousled, bleary eyed lot came down to breakfast the next morning.

For the next four months our routine was pretty boring, we did a few drills, and worked in the Office. Us Surveyors gave one or two lectures on Map reading to the Battery lads, we also did fire-watch duties in Napier Road. On one occasion I was roused by the fire brigade to inform me that the chimney was on fire. We spent our evenings in Edinburgh, at the cinema or a theatre, finishing up in some bar or café. Our guns were only in action twice in all this time.

We went on two or three long route marches of up to 12 miles, during these winter months, on one occasion were given raw meat and had to cook our own meal out in the open. It was a dreadfully cold damp day, and the only thing we could find to burn, and make a fire was some old roofing felt, which gave off such dense obnoxious fumes, that the meal was uneatable, and we smelt for days. Another time, the entire Regiment did a ceremonial Church Parade, down the whole length of Princes Street, two bands in attendance.

During this time, I had two leaves, the first was on the 14th of January 1941.

I left Waverley Station on the 5-18pm, and arrived in Newcastle at 8pm, but as I could not get a connection until 11pm, I rang Arthington to tell them not to wait up (it had been arranged that Mum and Dad would come up to Arthington, to meet half way).

I went out of Newcastle Station to look for somewhere to get support, asked an Old Boy who was standing around, he conducted me through the Blackout, down alleys, and small streets, then through a Newspaper Office and down into a Salvation Army Canteen, stayed there for a couple of hours, then went back to the station to catch the York train, this left on time and I then had a comfortable journey, as I was able to lay full stretch being the only passenger.

Changed at York, and had a cup of tea, and was able to catch the 1-55am Leeds train. It turned out to be a brilliantly moonlit night, a white frost seemed to illuminate the whole landscape. So I put out the lights, and opened the blinds, and watched the passing countryside. At Leeds I managed to get a good breakfast, and as the train for Arthington did not leave for another hour, decided to walk.

I started out across the moonlight City Square, continuing past the familiar buildings and traffic lights, and the ghostly white façade of the City Hall. It was so quiet, that the ticking of the clock up in the tower, could be clearly heard. Continuing past the University, across Woodhouse Moor, and on through Headingly, out into the Otley Road. Finally, on to Bramhope, turning into Creskeld Lane. Here again it was so quiet, that could hear the trains going into the tunnel, or perhaps the sound came up one of the tunnel air-vents. Arrived at the Post Office about 6am, and surprised to find Aunty Dot up and about.

Later in the morning I went round with the postman. Lovely scene from Bank Top across Riffa, to the fold in the hills at Fewston, reminding me of the times I’d been up here with Uncle and longer ago with Mr Chambers.

In the afternoon went into Harrogate, where I had arranged to meet Aunty for tea, I had to ask the way from a chap, who after telling me in great detail the way I should go, I had a lot of difficulty getting rid of. He told me that he was always showing people the way, and how easy it was to get lost in Harrogate, and that he knew seven ways, all different, to get to Knaresborough. He said that if it had not been for him, one lady, who was looking for the Post Office, would have been in Skipton by now.

I visited Eric’s parents at Almesford Avenue. It snowed heavily at night, but I was able to catch a bus back to Pool [Pool-in-Wharfedale].

The next day I went into Leeds and hired a Morris 8. From the size of the advert for this garage, I expected to find a big firm and a huge garage, but it turned out to be a one-eyed place, in a squalid part of Meanwood. Anyway, managed to get five gallons of petrol, and went off to Wakefield to see out old neighbours. I left Brook’s about midnight, and came back via Tingley, arriving back at the Post Office at about 2am. Once again Aunty Dot was still up. This time to tell me that Mum and Dad had arrived and that I had to sleep in the sitting room.

The following day took Mum, Dad and Aunty Dot for a ride round by Leathley, Buryemwick, Fewston, Norwood Edge and back via Ilkley. Dad and I climbed the Cow and Calf and then had tea at the Kiosk Café. The next day wasn’t such a good one: bitterly cold and a blizzard blew. Had to get the P.O. van to give me a tow to start. However, took everyone into Leeds, shopping. On Sunday the 19th of January, Dad, Mum and I had to return, snow had fallen all night, and it was lying in drifts, three to four feet deep. It was hard work walking to the station. Mum and Dad caught the London train at Holbeck, and I saw them off in the crowded, steamed up apartment, whilst I caught a train back to Edinburgh via Newcastle.

My last leave before going overseas, was on the 24th March. I arrived in London at 7.30am and wandered around the streets, having breakfast in Lyons in the Strand, afterwards I went on to Norbury. Mum and I went to Croydon; Kennards for lunch, and then to the pictures. One day I hired a car, and Mum and I went to visit Marjorie who was still in Cheam Hospital, and took her for a drive. We went to Box Hill, then back to Epsom for tea. The next day, Dad got the day off, so we went over to Tattenham Corner and walked over to Headley, having lunch at the Cock. The parrot was in good voice: Question: What is Hitler then? Parrot: A silly old bugger.

” Mum and I went to visit Marjorie who was still in Cheam Hospital, and took her for a drive “

On the 27th of March I returned to Edinburgh. Some Saturdays we used to go to a football match, and we saw Hibs [Hibernian] and Hearts [Heart of Midlothian], and Clyde, also witnessed the Semi-final of the Scottish Cup, which Hearts won, beating Celtic. There was plenty of cup-tie fervour from the spectators, and beer bottles were thrown at the wingers throughout the match.

On the 27th of March I returned to Edinburgh. Some Saturdays we used to go to a football match, and we saw Hibs [Hibernian] and Hearts [Heart of Midlothian], and Clyde, also witnessed the Semi-final of the Scottish Cup, which Hearts won, beating Celtic. There was plenty of cup-tie fervour from the spectators, and beer bottles were thrown at the wingers throughout the match.

At the end of April the Regiment packed up all its equipment, and we of R.H.Q. joined the convoy to the Glasgow Docks. We Surveyors were detailed as machine gunners as A.A. defence, and manned a Lewis gun attached to a precariously fixed bracket on one of the lorry tops. We had trouble starting, and so got left behind. Even the Colonel had a go at swinging the engine, eventually got going, and soon caught up with the rest of the convoy. We arrived in Glasgow at midday, right at the busiest time, but we had a Police escort, and just whizzed through the town, passing the towering red brick Grandstand at Ibrox Park, then on to the docks. There were tanks, planes, lorries, quite an astounding sight.

Surprisingly we left our vehicles, and returned to Edinburgh. A few days later all the Regiment returned to Glasgow by special train, and immediately went aboard a tender at Gourock, and climbed aboard the S.S. Aronda (10,000 tons), which together with other Troop Transports, was anchored out in the Clyde.

What a confused crowded place the Troop decks seemed to be. The first job was to collect our hammocks. What a game ensued when in the confined space, we tried to hang them. However, order was eventually brought about, fortunately we lay at anchor for three days, and by that time, we were familiar with the ship and routine.

We set sail at 8.10pm on the 26th of April 1941, it was getting dark and by the time we had cleared the boom, the detail of the coast had disappeared, only the outline of the hills were visible. Out to sea, the wind freshened and it became too cold to stay on deck. We went below, full of apprehension as to the voyage, remembering too well the possibilities of U-Boat attack.

The next morning, we went on deck, to a very cold, grey looking North Atlantic scene. The convoy comprised about twelve ships. Four were large liners, obviously Troopers, the rest Merchantmen, and two Destroyers, and were spread out in three lines, sailing on a predominantly westerly course.

We continued in this direction for the first week, and we all thought we were going to hit America. Everyone spent a lot of time looking over the rail, keeping a sharp lookout for signs of Submarines, or bombing Planes. Towards the end of the week the sea got rougher, and I succumbed to sea-sickness. A really miserable feeling, you just want to be left alone. I was not the only one, there were quite a few solitary huddled figures, squatting in out of the way places around the deck, with the occasional dash to lean over the side. The sight, or thought of food was enough to bring on the nausea, especially as the Mess Decks were in the forward part of the bows, and in a rough sea, there was a terrific rise, and sickening fall as the ship breasted the waves.

On the 2nd of May the sea became calmer, the sun shone, and we started to sail a southerly course, this made us feel much better.

The next day the convoy split. We continued South. It was rumoured that the other convoy was bound for Gibraltar, and history now confirms this. Five ships of the original convoy, containing a large reinforcement of tanks, was diverted through the Mediterranean, to make a dash for Alexandria. This was largely on Churchill’s initiative, after receiving a telegram from Wavell, stressing the gravity of the situation, owing to Rommel’s Offensive, which had taken him up to the Egyptian frontier.

” Our first sighting of land for twelve days “

The weather became consistently better, and on the 4th of May we changed into K.D., and started sleeping out on the Shelter Deck. Fortunately, we hung our hammocks in the roof of this covered deck, because; though unknown at the time, lascars used to swill the decks down, very early in the morning, and for those who elected to lay down their hammocks on the actual deck, it came as a rude shock to find water lapping around them, as only then did the Lascar, hysterically shout the warning, ‘Water come Sahib’.

The dim outline of land appeared at about 6am in the morning of the 9th of May. Our first sighting of land for twelve days. The land got closer, and mountains and jungle came into focus, we were soon anchored in the bay, about a mile offshore Freetown. The ship was immediately surrounded by natives, in narrow, dug out canoes, selling fruit, and diving for pennies, which when thrown over the side, could be plainly seen gently sinking through the clear sea. Most of the natives spoke English, apparently they cannot leave school until they have reached a reasonable standard.

The ship was here to get its coal-bunkers filled, and it wasn’t long before the coal barges came alongside, also bringing the coaling crew. These lads were an amazing sight, a hell of a motley ragged bunch. The first thing that struck us was that they all wore caps, of eye boggling variety, from floppy carpet material ones, to school boy caps. The latter were by far the most popular, and looked the most incongruous. Some had cap badges, and several had crossed cricket bat designs. After the coal-barges came alongside, two gang planks were fixed up from them to the deck. Then all day long, through the tropical heat, about thirty natives brought up a load of coal on their heads, running and emptying it down a shoot on our deck, and then down the other gang-plank and so on all day, with only a break at 2pm, for a bowl of maize. The heat was terrific, coal dust all over the place, and even at the end of the day, were still a smiling yet extremely dirty crew.

” These lads were an amazing sight, a hell of a motley ragged bunch “

After the extreme humid heat of the day, the evening was delightful, and as it got dark, the lights ashore came on, and you could see car headlights picking their way along the coast road. During the night there was a severe electrical storm, terrific lightning but no thunder. Eerie sounds came from the nearby jungle, and screaming noises, which we believed to be gorilla calls, could be plainly heard.

On the 14th of May we left port, and during that day’s sail, passed close to a half submerged life-boat. It was empty but had a jury mast, with an old vest attached to it. The fate of its occupants gave us food for thought.

We crossed the line at 6.48am on 16th of May 1941. To pass the time, Rig, Ridge and I started carving a set of chessmen from some apple box wood, this would keep us amused for a while. It is fascinating to watch the flying fish, the wash of the ship seems to frighten them, and when so disturbed they fly about thirty yards, and then dive back into the water. They cannot vary their height when once launched, as when a higher steeper wave comes along, they flop straight into it.

I have been in the Army one year on the 16th of May. It has really been a holiday so far, but a lot of wasted time. These days are spent reading, looking over the side and eating and sleeping.

We have now finished the chessmen, and they don’t look bad at all.

” Passed close to a half submerged life-boat, the fate of its occupants gave us food for thought “

We kept sailing South, and on the 20th of May changed back into Battledress, as the further South we travelled it became much chillier. The Plough constellation is still visible, and have now caught sight of the Southern Cross.

Had further inoculations, and didn’t feel so good for a day or so.

On the 25th of May we ran into very heavy weather, we estimated that we must be somewhere near the Cape. The wind increased to gale force and the seas became mountainous, spray came hissing over us from each wave crest. We were allowed up on the Promenade deck during the day, and had to hang on to life lines stretched to the full length of the decks. The view was superb, though the scale of it overawed us all. The other boats in the Convoy were plunging about, one of them showed her propellers every time she dipped over one of the gigantic waves. The seas calmed down during the night, and from that time on it started to get warmer again the further we sailed Northward and back towards the equator. Some lovely yellowish sunsets, and we got a glimpse of Table Mountain, low down on the horizon as we rounded the Cape.

By the 27th May we were in Durban and were allowed ashore almost as soon as we had docked. The ship was tied up alongside a palm fringed promenade, with white skyscraper buildings all the way along the seafront.

At night the place is brilliantly lit, coloured neon and fairy lights, enough light to read by. Food and fruit are in abundance, Rickshaws were everywhere. The natives who pull these, act like horses and shake their heads, and paw the ground, and prance up and down, to attract your custom.

Had our first drink of iced beer in the Twines Hotel. Then visited one of the many free Canteens. One of the girls took three of us to her home for supper. Her father was the Harbour Master (Pirens). The family entertained us to a meal, and we left just before midnight. As we approached the ship, what a scene! Like the retreat of a beaten Army. Some carrying a pal, or one helping the other, most of them tight as Lords. To the majority of them it must have seemed an almost impossible task to climb up the steep gang-plank, as the ship’s side really towered up sheer form the dockside. When we got onto our own deck, it was chaos, some being sick, some wanting to fight, others shouting and singing. It wasn’t until about 2am or 3am that things quietened down.

Next morning there was a route march, up and down the sea front. Rather a strange experience after our five weeks at sea. After this we went into town to the Royal Automobile Club, where we were split up into parties and the members took us out in their cars. We went with a Mr Taylor, who had originally lived in Portobello [in Edinburgh]. He took us out into the hills, stopping for tea in a delightful café. He then showed us the source of the Umengi River, then back to Durban via the beach. Afterwards we had a meal at the Playhouse Grill.

” Watching the dark velvet sky, with its numberless stars gyrating gently with the motion of the ship was and still is a magical memory “

After this pleasant few days we left Durban on the 31st of May, and sailed steadily Northwards, the weather getting hotter all the time. By the 10th of June we passed a group of barren islands, and even the wind was hot. We saw sharks for the first time, and could see their dorsal fins cleaving the sea. It was whilst we were cruising these equatorial waters that we spent unforgettable nights sleeping under the stars, on the top of one of the hatches. The Southern Cross was now plainly visible in the south east, and conjured up in the imagination the vast space of oceans across half the world.

Lying there on my back, and watching the dark velvet sky, with its numberless stars gyrating gently with the motion of the ship, indicated by the movement of the mast, the only sound being the breeze of our passage singing in the ships rigging and super structure, was and still is a magical memory.

On the 10th of June our table was awarded the ‘Cake of the Week’ presented by the Captain each week for the smartest and cleanest table. The system was that every day, after meals, all the utensils had to be cleaned and polished, then laid out on the table for inspection. This entailed quite a lot of work each day, as all the utensils used to bring the food from the central ships kitchen, for the ten men on each table had to be scrupulously cleaned, washed and polished. It was rather a nice fruit cake, but hardly worth the labour.

The 11th of June found us sailing a North-Westerly course, and we knew we were getting to our journey’s end, and on Friday the 13th of June we arrived at Port Taufiq, at the head of the Gulf of Suez. It was a flat sandy place which smelt of oil, and was full of shipping. The next day we disembarked, and were glad to get on solid ground, however dusty and hot.

We boarded a train: grey, windowless, wooden seated carriages, and were soon in featureless desert. The glare from the sand was terrific, and we were thankful when the line ran into the more fertile delta plain of the Nile. We eventually arrived at our Camp, which was on the outskirts of Cairo, and Beni-Yousef, right on the edge of the desert, within sight of the Great pyramid, at Mena.

” Our first visit into Cairo was a fascinating experience “

The camp was well off the Mena – Cairo Road – along tracks which followed the irrigation ditches, in a straight line for mile after mile. We passed native farmhouses where everything was very primitive: wooden ploughs, and water raised by Shaduf [hand-operated device for lifting water] in skin bags, in biblical fashion. Our tent was on the outskirts of the camp, and it was quite a strenuous march, through soft sand to the cook house. The food wasn’t so good: bread as hard as a board, baked twice, once in the oven and again by the sun, and liberally covered in dust and sand.

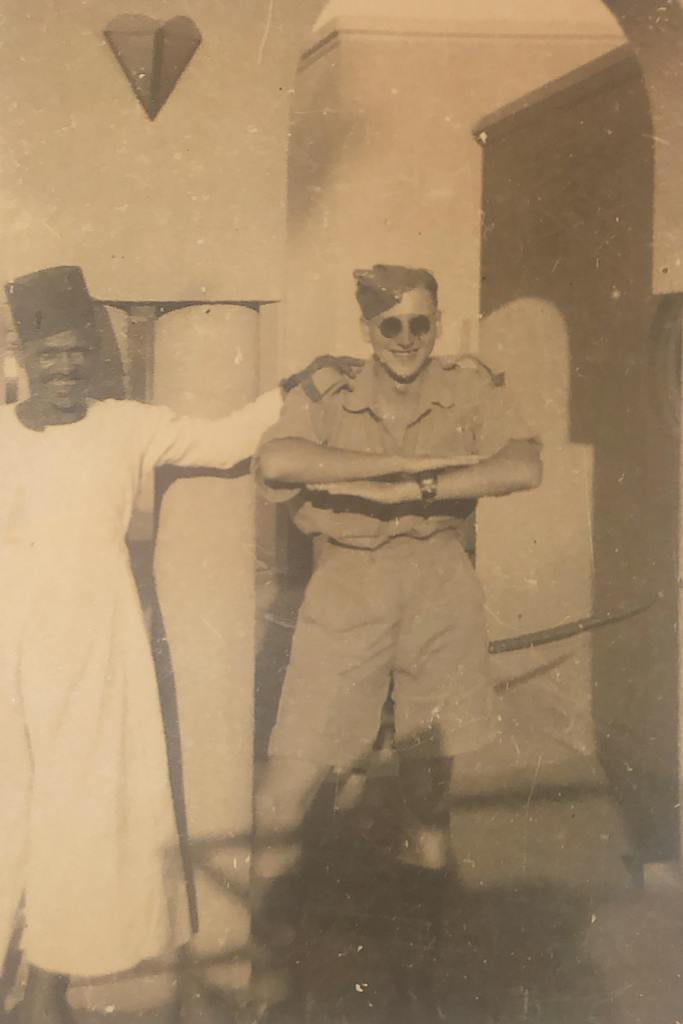

Every day we marched out across the desert. To get us acclimatised? It certainly made us sweat! However, Cairo was only a few miles away, and on our half-days off we made a bee-line for one of the many canteen and bar restaurants.

Our first visit into Cairo was a fascinating experience. The crowded narrow streets of the older quarter, and the strangeness of the dress and types of people. All the signs and street names in undecipherable Arabic characters, and the constant chatter of foreign tongue, all to be taken in.

We of course, by our pale skins, and new to the country were the prime targets for the innumerable street vendors and boot blacks [shoe shiners], who pestered us all the time. Even in crowded buses, they would crawl between the legs of the crowd, and appear before you asking you if they can clean your boots. Another trick was for them to slap a large dollop of messy black stuff on to your boots, and then you were forced to let them clean it off. We soon learnt to keep them at bay.

I put my name to a message, on the notice board at the Y.M.C.A., to contact Eric, who I knew was out here somewhere. At the end of the first week, on the 21st of June I had a reply from him. He is apparently out at Heliopolis, where we met, and had a good evening together. This was the first of many meetings, and had some enjoyable times drinking, eating, film, going on visits to the cabarets.

Our acclimatisation continued with route marches, and during this time we made a complete Survey of the camp and drew up the map. Our only measuring device was a home made chain, made of string and marked every ten feet, crude but effective.

” I put my name to a message to contact Eric as I knew he was out here somewhere “

We visited the Pyramids and the Sphinx and Mena and were shown the tombs, some of which were still being excavated. An old Dragoman [interpreter and official guide] took us into one of the Pyramids, and soon as he got us into the dark passage and we depended on the light from his candle, he demanded his money. We continued up a vast staircase, just like a Central Line escalator. Arriving in the Kings Chamber in the centre of the pyramid, the old boy, for a further few piastres [coins], lit a piece of magnesium ribbon, with dramatic effect.

After this we got a lift into town and had a swim at the Y.M.C.A. and after a few Zibibs [local Anise-flavoured spirit], returned to camp on one of the crowded Mena trams. These trams were single deck and ran along their own track alongside the road. For everyone who paid a fare, there were fifty who avoided doing so. The locals would clamber up the back and on to the roof, or just cling to the outside with one foot on some projection. This was a hazardous business, as sometimes when the tram got onto a very fast stretch of the track, the conductor, to discourage the practice of free rides used to lean out over the side and flail away with a cane hitting anyone within reach, as often and hard as he could, until the tram had to slow down to a speed, when his victims were safely able to jump clear.

Bad news from Oscar Hoskins who tells me that Lou Raphael had been killed.

Life for us continued serenely, we visited Cairo for food, a film and lots of drinks and ices. This went on for weeks, a constant round of entertainment.

We continued sightseeing too and one day a party of us: Stan, Brett, Rig, Mackintosh, and Inkster climbed the great pyramid, the one which has no facing stones on the summit. We approached from the unfrequented North corner. Here the blocks are in a crumbling state, but we managed to scramble upwards. Looking back from about half way up the height and our exposed position was quite alarming, it seemed decidedly steeper than expected and looking upwards at the top seemed to overhang. The summit, when reached was an area about thirty feet square with a flag staff in the middle, and the flooring stones are covered in names, carved on the surface of the soft sandstone. The view is huge, right across the Nile Delta, to the purple desert beyond. The line of cultivation is abrupt, no intermediate zone, the desert sand just starts and the greenery ends. The roads and drains appear as on a map and most of them are straight for miles. The descent was worse than coming up, and were well jolted by the time we got to the bottom. Each of the layers of stones, like huge steps each one being four to five feet high. Whilst we were up on the top, a light plane came buzzing round, to our amazement on one circuit it was lower than us, and we could see the top of the wings.

” The view is huge, right across the Nile Delta, to the purple desert beyond “

At last we got the order to move and on the 20th of September we moved up the desert road to the north, nothing but sand and heat haze. Crossing a belt of salt marsh, where the water appeared pink, we got our first glimpse of the Mediterranean. After two days travel we reached our camp at Ras-Hawala. A super place almost on the beach, among the sand dunes in the crook of a small bay, the flat curve of firm white sand ideal for bathing. The camp is approached from the road by a twisting track through the low stiff vegetation of the flat salt marsh. We spent the next ten days bathing. First dip 6am, the last at 8pm in the dark, beach-combing and eating.

The Surveryors’ duties here are on the Bren Gun, which we take in turns to man from dawn to dusk. Two rather unusual occurrences happened here. On the 23rd of September it rained like hell for a time, and the second, was that one day the sea was exceptionally rough, with great waves bashing up the beach. One of these turned me over and threw me up the beach, painfully sand-papering the skin off my backside. I had to have it pained with iodine. The medical Orderly thought himself some great artist, putting the finishing touches to some masterpiece.

” We got our first glimpse of the Mediterranean “

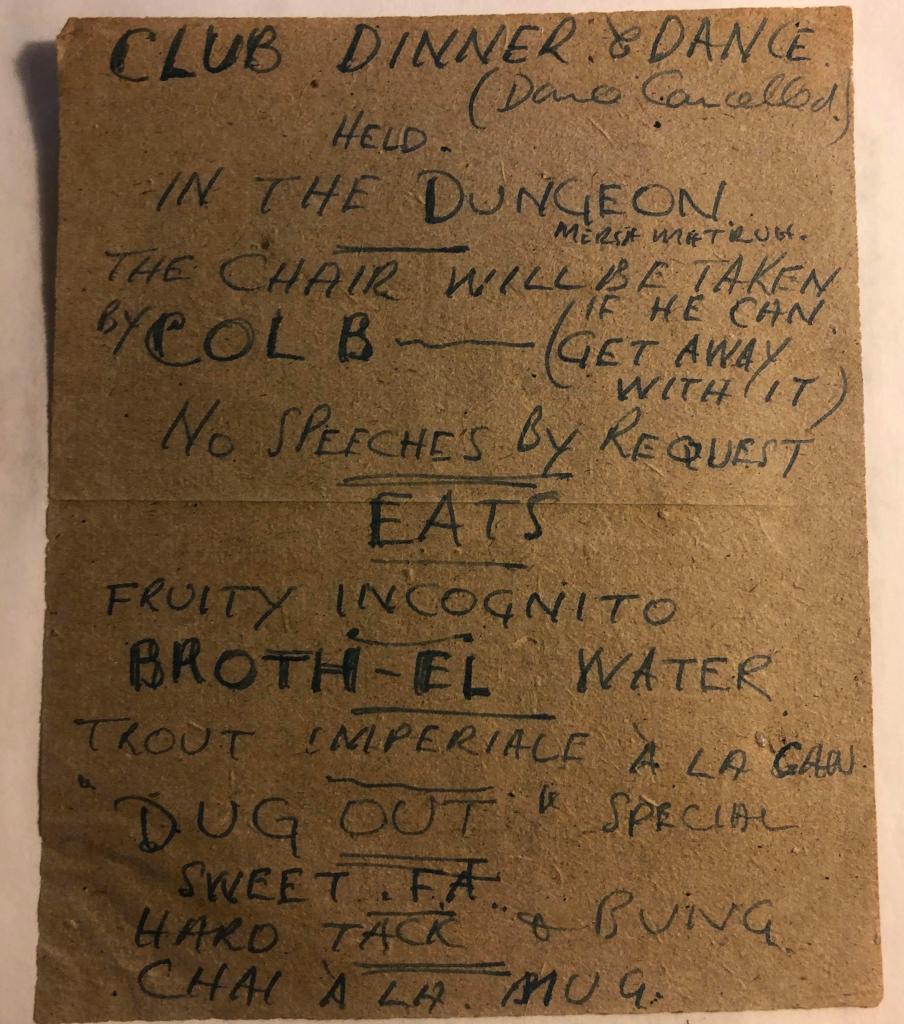

On the 4th of October we pulled out of this delightful spot of dazzling white sand and perfect blue sea with some reluctance, and travelled West, following the coast to Mersa Matruh. We settled in a Hotel right on the beach – The Lido.

The first task here was to build ourselves a dugout with a sand-bagged roof. Our stay here was short lived because on the 10th of October, Roger, Rig and myself were sent to separate Batteries. I was allocated to 261 Battery, somewhere in the desert near Sidi Barrani, and was put in one of the gun sections and on my first day we fired at a Jerry plane.

On the 11th and 12th we were again in action and fired eight rounds at single raiders, at extreme range, our shooting wasn’t too good. Had one nasty moment when one of the rounds fell off the ramming tray as Tex was about to ram it home. I picked it up, and at the second attempt it went home and was fired. It could have been a disaster.

A day or so later we had a dust storm which lasted about three days, and was really trying and most uncomfortable. This sand was particularly fine, and we had both the time and quantity to analyse it, finding, rather to our astonishment, that it contained far more than sand. There was a fair quantity of vegetable matter as well as parts of insects. This dust got everywhere, in your tea, clothes, tent, bed, nose, and eyes and stained everything a deep reddish ochre colour.

” On my first day we fired at a German plane “

On the 15th we took the guns out of action, ready to move and worked well into the night. The desert dust still blowing and no water to spare for washing. The next day the order to move was cancelled and all the heavy work entailed in putting the guns back had to be done again, in spite of the dust still blowing, and during this time there was a heavy shower, so that before long we had a paste of sand and water all over us, adding to our discomfort. But three hours later we had to take the guns out again, and at 1am we moved off into the desert, over very rough country, no tracks. We eventually kipped down for a rest but no hot food available, our only meal that day was breakfast when we had tea and hot porridge.

On the 17th of October we got into our new position. I don’t know how it was decided upon, as all that is to be seen in every direction, is the horizon, otherwise just featureless desert.

Within an hour of getting here, we opened fire. It took us a whole day of hard labour to dig a gun pit, as the desert is a rocky terrain.

Water and rations are short, and no chance of augmenting them in this wilderness. The bread, by the time we get it is dried out and the outside encrusted with sand and dust, which means that the outside slice has to be taken in turns, as one loaf has to be divided between the eight of us in the gun team.

One day, I went on the 15 Cwt Ration wagon to the aerodrome we are defending. All Fighters, Hurricanes and Tomohawks. All have shark teeth painted in the front of their fusilage. The guns were in action every day. One day, Jerry [German] fighters staffed the dome and we on No. 4 gun got 11 rounds off. First time we were given the order to fire independently, without the Predicator. The was because enemy planes came in low from many directions at the same time. We were told off for firing too low, and almost over the top of No. 1 gun, but pleased with ourselves for getting off more rounds than any of the other three guns.

The nights here are exceptionally cold, and we look forward to the warming brew of tea when we “stand to” at dawn.

Owing to our remote position it was difficult to get stamps for our letters home, I only managed to get one from a visiting R.A.O.C. driver during the last week. Water is also short and has to be made full use of, the ration is two pints a day, what remains after drinking we 1. Wash teeth 2. Shave 3. Wash face 4. Legs and feet 5. Towel 6. Socks.

” Unexpectedly, I was sent on seven days leave “

On the 30th of October we were peacefully resting at No.4 gun, when I was told to pack up my things, and taking to B.H.Q. to do some map drawing. I used the Major’s Staff car as a drawing Office, as it had a fold down table in the back. At night the Major’s driver (Dick Foley) and I used it as a sitting room.

A strange thing happened at this site. Dick took the Major out one day and it got pitch dark before they got back to camp, so dark that they could not see a thing, considered themselves lost and parked for the night. Next morning, they found themselves about a hundred yards from the gun site. This speaks well for the full-site blackout discipline, the quietness, and the camouflage.

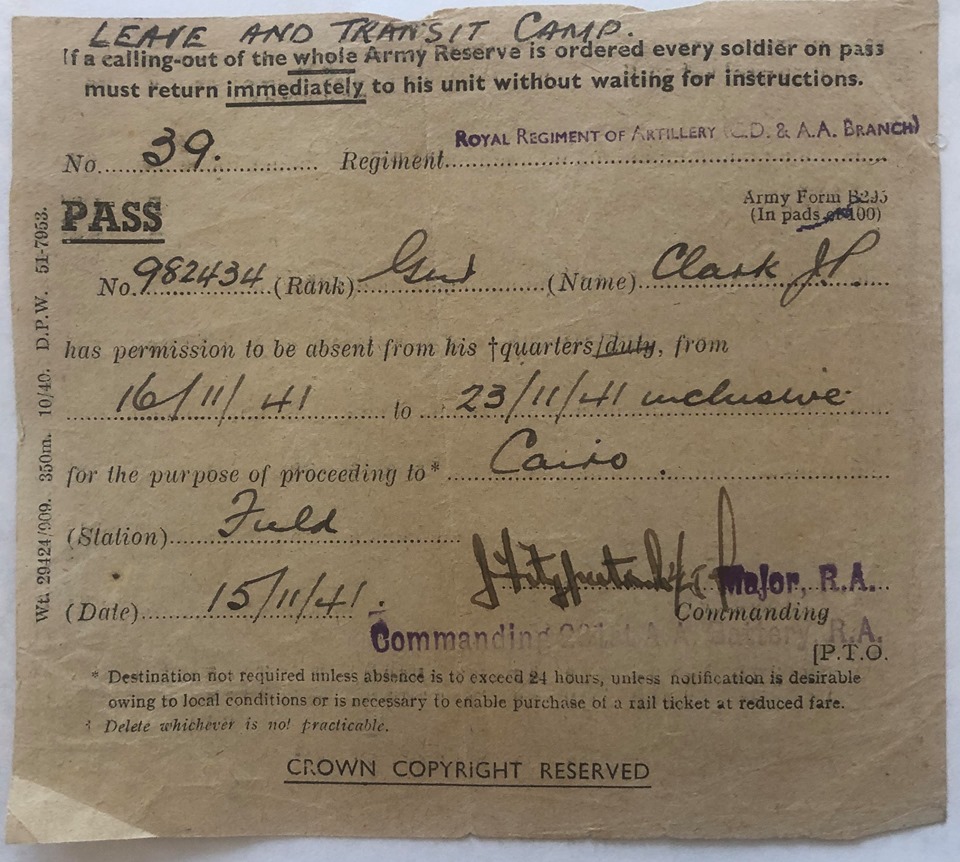

Unexpectedly, on the 14th of November 1941, I was sent on seven days leave. Bounced and shaken over fifty miles of desert to Matruh and from Matruh and Cairo by train. As soon as we arrived we were surrounded by hotel touts. We decided on a hotel in Opera Square.

Met up with Eric at Heliopolis.

Operation Crusader started on the 18th of November, and news of our advance trickled through to us even in Cairo. Didn’t relish the journey back after this leave, as I had developed a bad head cold, so bought half a bottle of whisky for the journey. The train was packed and so had to sleep on the floor, with someone’s feet dangling over my face, I was thankful for the whisky. It was still an uncomfortable trip and was glad to arrive at Mersa Matruh after 19 hours on the train.

Just as I was leaving Matruh with the rest of the Battery lads, I was told to get off the lorry and report back to R.H.Q. I did this with mixed feelings as didn’t think it would be the same as before. However, a few of my old pals are still here and it is certainly an easier life. So it proved: we were bathing every day though it was almost December.

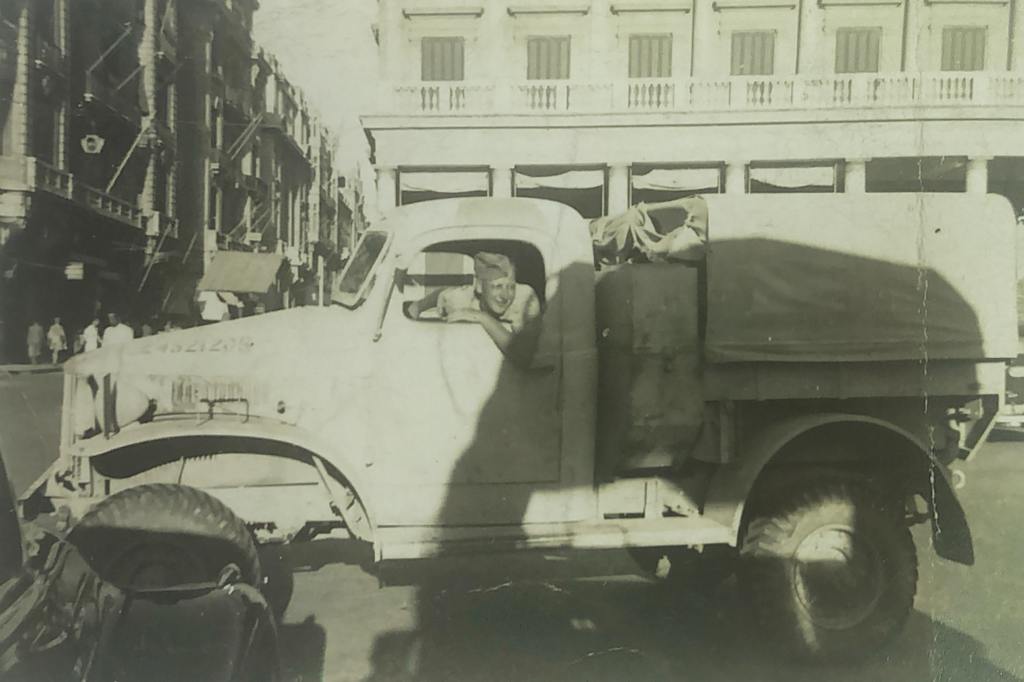

Now that I was back at R.H.Q. there was still nothing specific to do and I used to go with Stan to the water point each day to fill up the water tank on the 30 Cwt Bedford. This truck was nicknamed ‘Waltzing Matilda’ as at high speed the water used to swill about, making the truck swing and sway all over the road. The trip to the water point took us along a deserted coast road, and as we went along we used to fire at the old milestones and road signs, or the post on which they once stood, and they were soon riddled with bullet holes. At this time we acquired a captured Italian Motorcycle, and tore round the town for fun.

On the 6th of December we had an Air raid. Also today a German General prisoner arrived, and our Colonel had to escort him to Cairo. When he came off the ship here, he only wore a shirt and as he got into the car even his balls were visible. He had been torpedoed and picked up at sea apparently.

Our easy life continues, nothing much to do but wait. We gather in the dugout every evening and yarn and cook a supper on a Primus, our supplies kept in a secret place under one of the stairs down to the dugout. On the 19th of December we get news that we have taken Derna and, on the 22nd a captured Jerry [German] mark 11 came through. Painted with greetings for Christmas from the VIII Army, on its way to Cairo, as a present to General Auckhinlech.

” Christmas Day was gloriously sunny “

Christmas Day was gloriously sunny and we had a bathe. Dinner was stew but the pudding proved to be the real thing. Quite a lot to drink, this led to arguments between the English and Scots. Bottles were thrown and Woody knocked huge lumps off the Canteen counter.

On the 29th of December we were all ordered out on a three-mile route march, some effort to get rid of the Christmas hangover, no doubt.

New Years Eve came along and ugly scenes ensued, after the drink had taken effect. We adjourned to the dugout for a private party and saw in the new Year with a bottle of Port and slices of cake, supplied by Rigs parcel from home. I thought I’d be clever and take advantage of the noise and drinking, to make a raid on the cookhouse to get some spuds, but I ran into a post and split my head open, so went to bed but not to sleep as we had drunken visitors until 3am.

We were also asked to put up a visiting Sergeant in the spare place in our dugout, but he didn’t stay. We later learnt that he had gone back to the R.S.M. and said he wasn’t going to sleep in the place because there were potatoes in his bed. Apparently the R.S.M. took it that he was suffering from D.T.’s, but the joke was that this Sergeant was the only sober bloke at R.H.Q. that night, the potatoes were real, in fact the ones I’d raided from the cook house. The next morning, as seems usual with this Scottish Regiment, nobody was fit for anything, even at 9am there was nothing stirring in the cook house.

” We saw in the new Year with a bottle of Port and slices of cake “

The weather turned pretty cold and some rain fell, but the scene on a moonlight night was glorious. Especially from the machine gun post on the Lido roof, a converted water tank, well sandbagged. From here we have an uninterrupted view across the bay and over to the high white coastal dunes. Still cooking suppers, and have now made an oven. We have also rigged up a huge canvas sheet in an experiment to catch rain water.

A South African concert party turned up, it was a real fight to get in. The girls were greeted by noisy wolf whistles which never died down. One act was by three acrobats, but owing to the very low arch over the stage most of the best action was out of view, above the top of the curtain. At this period, we Surveyors were in charge of the Armoury and took it in turns to sleep over in the cellar of the Hotel, where our small arms and ammunition were kept.

” The scene on a moonlight night was glorious “

Another of our projects to pass the time was the opening of the only Golf course in this part of Africa. The clubs were home made from date palm branches, and the balls were cut from solid rubber. There were no greens, as such as sand was everywhere.

Note: Machine gun post on roof and our reinforced dug out in bottom left corner

Taken from the Lido roof

The 22nd of January brought news that a battle had begun and that we were not doing so well. Some South Africans from a Light Armoured Corps, told us of a skirmish near Antelat, lots of dead and tanks ramming each other. One of them telling us how he killed his first German, very artistically apparently, with a hand grenade. We also saw a large number of recovery vehicles, bringing damaged tanks back from the front. We had several air-raids, and on one occasion Rodge, who was up on the roof with the Bren gun, shouted something down to us, immediately everyone dispersed like rabbits to cover, but it turned out that all he was doing was warning us that one of the footballs was being blown into the sea.

Early in February the news came through that a section of 261 Battery had been captured, including Dick Foley and the Major. There had been an unexpected German breakthrough by an armoured force, they were surrounded and couldn’t get their guns deployed in the anti-tank role, quickly enough. I thought, that there but for luck, I too should have been among them

” I thought, that there but for luck, I too should have been among them “

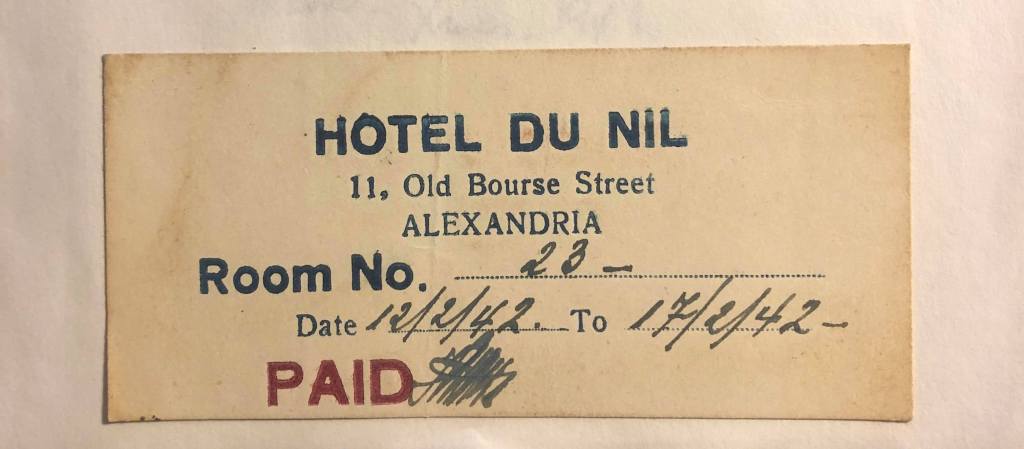

From the 11th to the 19th went up to Alexandria on leave. Met G.L. Wood, who is with the 1 Div Tanks. He told me that the sad news that Oscar had been killed, a great blow that.

On my return to Matruh they were all talking of the attack, the night before by torpedoes, fired from out at sea by submarine. Three torpedoes had been fired through the narrow harbour entrance, one of which had failed to explode and came right up on to the foreshore, and next day the naval people came and removed the charges and set fire to them on the beach about a quarter of a mile away, the heat from the burning explosive was almost unbearable even at that distance.

At the beginning of March, we had a boisterous spell of weather and even a few showers, and to our amazement within forty-eight hours there was a carpet of wild flowers in full bloom in the usually bare Wadi. Poppies, Dog-Daisies, and Milkmaids, also a fantastic sight of hundreds of wild geese flying high in the clear blue sky forming and re-forming into V and W formations. At intervals their throaty calls could be heard, on their way north to their breeding grounds in North Russia.

For the next month we just hung on in Matruh. Amusing ourselves on various projects, we made a diving raft, and tried to renovate a damaged boat. We even tried to make a boat out of corrugated iron, which on its first trial sank. This even amused the Colonel. Spent a lot of time fishing, sometimes with hook and line or in a highly exciting fish drive, at a place where at low tide the water rushed out through a narrow culvert from the vast salt lake. We caught grey Mullet, and it was excellent eating. There was also plenty of Octopus here, though we never tried them, but we did have several feeds of Shrimps.

February 1942

On the 19th of April I was asked if I would be the Doctor’s driver, and as there was no Survey work, agreed and took over the Dodge Pickup. Had a drive into Alexandria with one of the Officers, and went all over that town, Mex, Kom-el-dikka, and Hamra, came back the next day via El Daba. On the 17th we left Matruh and moved up the desert road to defend one of the forward Fighter Dromes. It was stifling weather for convoy work, the roads were packed with other troops, so we were glad to pull off the road for the night near Sollum, just before the road starts to climb the escarpment.

The next day we crawled up the Halfaya pass which loops up the cliff-like escarpment in several steep hair-pin bends, with a gradient of about 1 in 3. To make matters worse a sand storm blew all day. We turned off the road at Gambut and followed the desert track, putting up camp close under the shelter of a rocky sided Wadi, where the low escarpment outcrops. The rest of the country is flat as far as the eye can see and is covered with little mounds caused by sand accumulating in the small shrubs, which grow all over the surface, green now, but the sun will dry the vegetation up.

Plenty of evidence of German and Italian occupation, wrecked tanks and motor vehicles. Over on the northern horizon, we can see through a shimmering dusty haze, the tents and G.L.s of the Gambut Landing Ground and see the Hurricanes taking off and landing.

We were soon dug into our position, the sand was free of rock and so we were able to easily get down at least three feet, safe from air attack and straying tanks of our own. Everyone used to congregate round the Office lorry at 6pm to listen to the news.

“Everyone used to congregate round the Office lorry at 6pm to listen to the news”

One day an Arab camel caravan passed, headed by two men and three women, the women gaily dressed in bright colours and riding donkeys. A string of camels following in single file, some laden with bulky loads. One of these camels took fright and ran amok. It must have objected to carrying such a big load, it bucked and bumped until the load came off, then it disappeared into the distance with the camel drivers racing after it. They eventually caught the animal and reloaded it, amidst bad tempered grunts and groans.

My main task these days is to maintain the Dodge, this entails mainly replacing road springs as the terrain around here is very rough. I also run a Taxi service for the Sergeant who services the G.L.s (Radar) which are set up round the Landing ground.

April 1942

On the 15th of May, whilst burning some rubbish there was a dull explosion in the fire, at first thought we were being sniped, and when I looked down there was a gaping wound on my left arm. I was rushed over to the Medical lorry, then had to go on to Field Hospital, just along the ridge. Here I had an X-Ray, and they found a piece of jagged brass about ¾ of an inch long.

In no time at all I was given an anaesthetic, and had the splinter removed. The other inmates of this tented Ward were all looking forward to me coming round, as the effect of the drug usually promotes exceedingly bad language, as the patient recovers. I stayed here for several days, until the wound was healing. The chap in the next bed, was a French Foreign Legionnaire, for Leclerq’s Army, though he was a Russian. He had a mild and amiable nature, unlike what you would expect in a Legionnaire.

The cause of my accident was a round of .303 ammunition, which I kept in my pocket and used to strip and clear the Lewis machine gun, but unfortunately I’d left a round in a pair of old dungarees that I threw on the fire, the bullet had exploded, and I was lucky that the piece of the casing only passed into the fleshy part of my arm.

” There was a explosion and when I looked down there was a gaping wound on my left arm “

On the 27th of May, I had to leave the Hospital in something of an emergency, and the Regiment had to hurriedly pack up, and move not west but east. Rommel’s forces had attacked and outflanked the line at Bir Hakeim and was advancing on Tobruch. We moved at night, even so we were staffed by German Fighter Planes in the moonlight. We eventually halted and dug in, and here we stayed until the 12th of June. All of the driving I’d had to do didn’t help my arm to heal, in fact it opened up again, so was glad of the few days rest.

It was whilst we were waiting at this camp near the Egyptian border that Rig said his farewells, broaching a bottle of Dewars to celebrate. We drank his health in the moonlight, and next day I took him to the Railhead at Metruh. Then had to get back to Capuzzo on the way having a refreshing swim at Sollum.

There was an amusing incident here wen one of our drivers had to go to this Capuzzo base for stores, Inkster (the canteen wallah) told him what to buy, and said that there were a few pounds over and to use his own initiative as to what to get. It proved a tremendous problem for him and he finally decided on a huge case of Andrews Health Salts. One man’s luxury is another man’s laxative!

” We were staffed by German Fighter Planes in the moonlight “

Water was short here, so we located one of the old desert cisterns, but the enemy had salted it. However, collected it for washing purposes. It was an interesting place, just on the edge of the rocky escarpment, the only clue to it was a stunted Fig tree. After searching around we found a small square opening cut in the rock, only big enough to get through and once inside it was about six feet deep and roughly ten feet square with a stony bottom which held a few inches of water. It was hard work lifting four gallon cans of water through the hole in the rock ceiling, but a tin of water thrown over us was most refreshing and revived our flagging energy.

On the 7th of June drove into Tobruch. It seemed most incongruous to be in a town and see people walking about on pavements and to see shipping in among the harbour buildings, after coming in from the featureless desert. The noise of the battle still goes on from the direction of the ridges at Knightsbridge and El Adem.

Just before the evening meal on the 14th of June the word came to move. This time we moved off further east, travelled until dusk and stopped to make a meal, then onwards, or more correctly, backwards.

We caught up with the main convoy at breakfast time after a night journey. After breakfast we crossed the wire at Sidi Omar, back into Egypt. We continued across the desert for another five hours, and never saw another vehicle in all that time. At midday the heat was stifling and the engines were overheating badly, the metal of the vehicles was too hot to touch. We drove all day on a compass bearing and churned along through many types of terrain. The worst, was an area of stony desert closely strewn with polished black rocks, each about as big as your head. This lasted for miles, and to our amazement the tyres stood up to it.

Driving became really exhausting, and when we halted for a rest there was no shade and with the vehicles giving off so much heat like hot radiators, even then it was cooler under them, than out in the sun. At the end of the day we were so shattered that we just put down a blanket and fell asleep. The next day we dug in and started surveying gun site positions on a landing ground to replace those we had had to abandon.

After five days we again got the order to move. Not surprised as the news from the front is not good and on the 21st Tobruch fell.

” We saw on the horizon ahead the reddish glow of bursting bombs “

On the 23rd of June we moved off further east, through Matruh, where we passed the New Zealand division, moving up to occupy the Mersa Matruh defence box. The roads were absolutely choked with vehicles going in both directions. Camped on the coast near Daba, and the next day surveyed three gun sites around the El Daba airfield. After a day surveying in the desert it was marvellous to get back to camp on the beach and have a bathe. The white sand and breakers delightful to look at in full sunshine or under moonlight.

The military situation didn’t seem to worry us very much.

However, on the 28th we moved east again. Jerry now close to Matruh, and we travelled all through the night. Just as the moon came up we saw on the horizon ahead the reddish glow of bursting bombs, this got nearer as we travelled, and we realised that we should have to run the gauntlet, as the bombing was at a place where the road crossed the railway, and there was no other way round.

Before we got there we were spotted and a plane came up on the right and turned ahead of our convoy and came hurtling back and raked down our left flank with machine gun fire. I could see the tracers hitting the road well ahead and hastily stopped the vehicle and dived underneath, but in my haste I had forgotten to put on the hand-brake, so had to just as hastily get back in the driving seat again, by which time the danger had passed and luckily didn’t get hit. The Doc in the passenger seat wondered what was happening as he had been fast asleep and had not come to enough to get moving.

We were about to cross the railway when the bombs came. We got as far as the crossing when a stick of bombs exploded close behind us, we breathed in relief when we saw the last of the line burst, just then another plane swooped in and straddled the convoy. One of these burst on either side of the fifth vehicle ahead of us. Fortunately, the track was through very soft sand and though it meant that we could only grind along in first gear, the splinters didn’t fly, but it was too near to be pleasant, and had to trust to luck as some of the vehicles had been hit and were on fire, providing the enemy planes with a clear view. In fact we got a superb view of the bomber as it banked low above us, we could see the underside illuminated by the fires below, and lights showing through the open bomb bays.

After this we kept our heads down and eventually arrived at our destination early on the 29th of June 1942, at a camp on the Cairo to Alex Road.

The amount of motor transport assembled in this area was incredible, but within a day things had been sorted out, and we started surveying a landing ground at Karm Quattara to fix the gun sites, and were soon organised enough for us to have trips into Alexandria for haircuts, drinks, eats, and cinema shows. A squadron of Spitfire fighters were exceptionally busy from the airfield just across the road, and we were fascinated to watch them taking off, and landing until it was practically dark. How they could see the ground at such times I do not know.

” We were about to cross the railway when the bombs came “

One night I had to take the Doc to a Battery in the desert. We didn’t leave until 1am, in the pitch darkness I drove over a slit trench, the Doc had his head out of the side window at the time trying to see where we were going, and as the wheels went over the trench his head went up and down like yo-yo, between the roof and lower sill with some force. Luckily he was partially insensible with drink. Further on I almost drove through a Bedouin tent but saw it in time and backed off, though not before we had disturbed the inmates, together with several chickens and dogs. Eventually arriving back at our camp safe and sound.

I was usually detailed to take the leave Truck into Alex and one return journey late at night swerved, at a point where the tramlines diverge and continue on their own separate track. In the gloom I didn’t see this until too late and had to swerve rather violently to keep to the road. One bloke fell off, he was the only sober one aboard, he grazed his hands and knees badly. He afterwards complained of a back back, and even tried to get invalided out of the Army because of it, though without success, or sympathy. On the 23rd of July went to 261 Battery for four days who were up at Borg el Arab, and did some surveying.

At the beginning of August we helped on a big scheme to make a “going map” across the desert, from Wadi Natrun on the Cairo to Alex road, due west to the Quattara Depression. I think this was part of a big bluff to make Rommel think that when the Offensive came to break through the Alemein Line, it would be from this direction. However, we had to sit in the back of a three tonner, which was one of a line of twelve such Lorries arranged about four hundred yards apart. At the given signal the whole line moved forward and notes were made of the surface of the desert every quarter of a mile as called off the speedometer. During this exercise we came across an interesting Coptic Monastery, isolated in the desert in Wadi Natrun. We talked to some of the Monks who were very interested in Diesel engines, and were very knowledgeable. At one place here the G.T.V.s got stuck. These heavy vehicles went through the dry salt crust of the Wadi, into the mud. I was sent on foot, across the desert to get help.

Another project was to erect a target for the 3.7 A.A. guns, consisting of large oil drums, 8 drums high, to practice firing A.A. guns at Tanks. The Germans had already begun doing this very successfully with their 88mm for some time.

Towards the middle of October, we did a lot of surveying forward, so that the guns could go into marked positions as soon as the attack goes in, to defend the forward landing grounds.

On Friday the 23rd of October we were briefed on the forth-coming battle, and at 4pm that day, Rodge and myself went off to the forward sites. At 10pm the Artillery barrage started up and the flashing and noise went on all night, this together with sweeps of Aircraft created a terrific din. Both we and the enemy certainly knew that the big battle had begun. The gunfire and Air activity continued next day. Stan came back from the water point saying that he had seen lorry loads of Jerry [German] and Iti [Italian] prisoners. Whilst we waited to join the advance we discovered a fig orchard in the desert somewhere near Borg El Arab, and picked a whole bucketful, which Stan made into jam.

On the 4th of November we joined the stream of traffic to the west, past Alemein Station and on to Tel el Eisa, where we parked for the night through Diamond Gap in the mine-fields and just in front of an Australian 25 pounder Regiment, who were still firing at the Germans in the ‘pocket’ on the ridge.

Early next day November the 5th, the fireworks started before dawn and as it got light two Messerschmits dived in and dropped their load. After this we pulled out and advanced to El Daba. Here the roads were littered with dead Germans, wrecked tanks and lorries, also one or two abandoned 88mm Gun emplacements. At these places we had to swerve from side to side to avoid running over the dead. We later came up to a convoy of Australian infantry, who were going back, one dressed up in Italian General’s uniform, and displaying hands with gold rings, presumably looted from the dead.